“Don't sing love songs, you'll

wake my mother”

— Joan Baez, “Silver Dagger”

(1960)

The German martyr Dietrich

Bonhoeffer only served once in a pastorate, for about 18 months at a Lutheran

Church in London in the 1930s. Thanks to Charles Marsh’s brilliant biography

Strange Glory, I learned, among other things, that the young preacher made sure

to ship to England: his piano, his phonograph, and his record collection.

It seems the church manse doubled

as a casual cultural center or bachelor pad. An average day there, according to

Marsh, looked a little like this: a late and lavish breakfast, a few hours for

work on sermons or other tasks, fellowship with friends that always included

piano playing, frequent trips to theater and cinema, and late, late nights of “meditation,

music, theology, and storytelling.”

Marsh’s beautiful book is a

courageous corrective of the conservative revision of Bonhoeffer by Eric

Metaxas, which somehow made the German martyr into a right-winger like Metaxas

himself. Marsh also came under some criticism for noticing unrequited

homoerotic overtones in Bonhoeffer’s lifelong friendship with Eberhard Bethge.

What we also learn is that for a

Christian theologian as serious as Bonhoeffer, who gave his life fighting

Nazis, there was a flavor of Protestant monasticism that emphasized sport and

spontaneity, music and art, playfulness and pleasure—and passionately

opinionated without the hypertoxic mansplaining that has infected more macho

evangelical circles today.

When studying in America,

Bonhoeffer spent considerable time worshiping in black churches and collecting

albums of black music that he would find in Harlem record stores. Some of the

German writer and resister’s favorite songs were “Go Down Moses” and “Swing

Low, Sweet Chariot.” Bonhoeffer knew Beethoven, but he also needed black gospel

and blues.

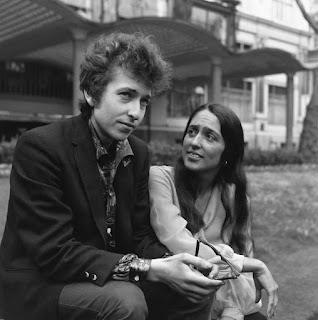

Martin Luther King Jr. had

well-known friendships and collaborations with the likes of Mahalia Jackson,

Joan Baez, and Nina Simone, all famous female singers, some 50 years ago. The

1960s did not just have a revolutionary soundtrack for the hippies with Beatles

and Byrds, Airplane and Stones, it also had the folk and soul music that

motivated the Civil Rights movement. The 2014 film Selma depicts Martin

Luther King calling Mahalia Jackson late at night, just so she could sing to

him over the telephone.

The Kentucky monk and prolific

poet-essayist Thomas Merton was obsessed with music in the mid-1960s. Fans of

Merton’s books will be grateful for the unconventional biographical sketch we

find in Robert Hudson’s new book The Monk’s Record Player: Thomas Merton,

Bob Dylan, and the Perilous Summer of 1966. Merton had his friend Thomas

Waddell procure albums in which to immerse himself at the Gethsemani Monastery.

On tap was Highway 61 Revisited by Bob Dylan, a musical and literary

text that provided a perfect “surrealist” and “kaleidoscopic” summer soundtrack

during a blissful but tumultuous time for Merton.

Don’t let the modest robes fool

you. Merton spent his last years on earth as a public intellectual and

cosmopolitan badass. Taking notes, not just from his biographers, but from his

journals, we glean a hip and complicated Merton as cool cat, getting his head

bent on black free jazz and free-flowing booze. I have a favorite picture of

Merton in a trucker’s cap and holding a can of beer on a warm day. After Merton

moved into his hermitage, many friends would sneak onto monastery grounds by a

shortcut, bypassing any official gates, to hang out at the hermitage with

books, music, and conversation, always well-spiced with good food and drinks of

an alcoholic variety.

Even before Merton got his

headphones full of Dylan, his ears were already attached to Joan Baez. Her song

“Silver Dagger” took on special significance. “Silver Dagger” was Joan’s

opening track on an eponymous 1960 LP.

You see, this spring of 1966,

Merton met a woman named Margie (and often referred to only as M.), when she

served as the author’s nurse, during a stay in a Louisville hospital. Both

because of Merton’s vows and because of his honest diaries, we know the brief

romance is more mysterious and emotionally intense than the average affair.

This topic has troubled and titillated Merton’s fans and scholars since, but

Hudson is the first to discuss it in the context of Merton’s music fandom.

So back to “Silver Dagger.” The

song goes something like this: two-and-a-half sensually tortured minutes of

handsome heartbreak, unfulfilled passions, and lost loves.

It is not a courtship song, not a

wedding song, not even a track most of us would associate with romance at all,

except in all the ways that great folk and blues are often fraught with

romantic tragedy. And somehow, it is the perfect song for Merton and Margie’s

deliciously doomed dalliance.

So here is Merton, his ridiculous

rising hour (the middle of the night for normal people) is the same time Margie’s

shift ends at the hospital. So they agree like teenagers (she is younger than

him, but they are both older than teens) to listen each morning, at precisely

1:30am, to the song “Silver Dagger” by Joan Baez. It is a simple and touching

ritual of infatuation meets music fandom.

Many couples in the fresh stages

of new love find themselves reeling from similarly important gestures.

Thankfully for many couples, though, there future love is not as fated for

heartbreak as this sad and lonely situation, this season of dreamy intoxication

that takes over the thoughts of this passionate American monk.

Scholars have suggested that the

world is blessed by Margie’s modesty. Apparently she moved on, married, had a

life. She never discussed this affair; there was no memoir. We are left with

Merton’s confessions and the

sense that he ended the romance before it got out of hand for either

participant.

We have no first-person diaries

discussing Martin Luther King’s allegedly wild sex life, but his legacy is not

so fortunate as Merton’s on this count. Several books detail what we know about

life-on-the road with King’s inner circle. It was a party. Late nights of

eating, drinking, laughing—and loving.

On Martin’s last night on earth,

after fighting a cold, after giving one of the most powerful and prophetic

sermons in a career of powerful and prophetic sermons, Martin King and his

brother

A.D. stayed up all night partying

with their respective lovers.

It was not the loyal and loving

Coretta, but King’s girlfriend and Kentucky state senator Georgia Davis, who

was in his hotel bed the night before he died. As we remembered the 50th

anniversary of King’s tragic death earlier this year, I read Davis’s memoir

about her relationship with King, and her discussion of that fated week in

April 1968 was almost too much to learn, even for a King fan and scholar who

has never had blinders on about Martin’s sins.

We know that both Dietrich

Bonhoeffer and Martin Luther King Jr. were revolutionary Christian martyrs who

died resisting injustice. Both were murdered at age 39, in the month of April,

in the season of Lent and Easter when we commemorate the crucifixion and

resurrection of another revolutionary named Jesus. Thomas Merton died in

Advent, also in 1968, and he was a little older at 53.

Merton’s death had long been

viewed as an accident, but a new book, The Martyrdom of Thomas Merton: An

Investigation by Hugh Turley and David Martin, suggests otherwise.

Commenting on the book, mystic author and correspondent with Merton, Matthew

Fox says:

“So Thomas Merton, Cistercian

monk and one of the greatest spiritual writers of the twentieth century, died a

martyr. A martyr to peace (because he was a loud voice against the Vietnam War

and a mentor to the Berrigan brothers and others committed to nonviolent

protest). And he died at the hands of the American government in the very year,

1968, that Martin Luther King Jr and Robert Kennedy also suffered a similar

fate.” Time will tell if other Merton scholars will take up this theory, but so

far, the reception of the Martyrdom book has been a mixed bag.

Bonhoeffer, Merton, and King.

Christian practice in the 21st century can only benefit by learning more and

more about their Christian witness in the 20th century. I would say that all

three, they were all revolutionary mystic saints, but they lived complicated

and messy lives, mysterious lives with unbelievable soundtracks.

Celibacy or lifelong monogamy are

held up as Christian ideals, but the reality for many Christians, this

reality looks messier and more

complicated. The power of passion permeates the lives of the 20th century’s

broken saints, and for them, romantic passion was a complicated part of life’s

larger passion for the gospel, all of these mediated by the healing and hopeful

power of popular music.

— Andrew William Smith

Comments

Post a Comment